What Does Success in the Arts Look Like? - Interview XX with Carla Gannis

/Carla Gannis - Artist, NYC

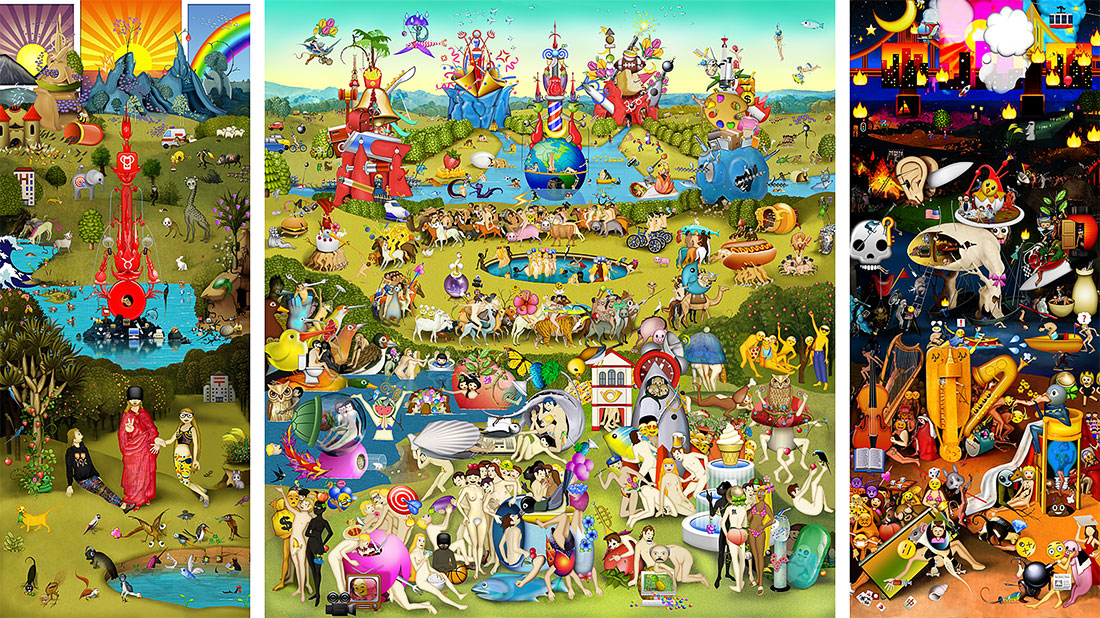

Carla Gannis is a New York-based artist fascinated by digital semiotics and the situation of identity in the blurring contexts of physical and virtual. She received an MFA in painting from Boston University, and is faculty and the assistant chairperson of The Department of Digital Arts at Pratt Institute. Upon her arrival to New York in the 1990s, Gannis began incorporating digital elements into her painting-based practice. Since then she has eclectically explored the domains of “Internet Gothic,” cutting and pasting from the threads of networked communication, online art history, and speculative fiction to produce dark and often humorous explorations of the human condition. She received widespread attention in 2013 for her emoji version of Hieronymus Bosch's Garden of Earthly Delights.

Her work has appeared in numerous exhibitions and screenings, nationally and internationally. Recent projects include “Portraits in Landscape” Midnight Moment, Times Square Arts, NY; “Sunrise/Sunset” Whitney Museum of Art, Artport; and “Until the End of the World,” DAM Gallery, Berlin. Gannis’s work has been featured in press and publications including, ARTnews, The Creators Project, Wired, FastCo, Hyperallergic, Art F City, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and The LA Times, among others.

***

What are your thoughts on fame in the arts?

It is a beguiling and seductive premise, art fame, but there are certain varieties that can become increasingly lackluster when viewed from a distance. On the outermost ring of concentric circles orbiting the elite art world nucleus, even Damien Hirst’s diamonds shine less brightly.

I grew up in a small town where only few people knew the names of any “famous” living artists. This was pre-World Wide Web, but if I were to return there now, I doubt contemporary artist recognition would be significantly improved. Recording artists and performing artists have mass populist appeal, but the arts I’m referring to, where artists garner success through museum acquisitions and auction house sales, still resides in a more rarified domain.

Let me think about the art world by referencing the planet Saturn: there are seven rings made up of an exponential number of smaller rings representing in my metaphor the numerous art worlds that exist. Multiply the number of satellite art fairs at Art Basel Miami times ten thousand and you get the picture. Of course MoMA, Gagosian, David Zwirner, Saatchi, Sotheby’s, Christie’s, etc, etc…have real estate on Saturn, but on each of the surrounding rings, there are galleries and non-profits and apartments and garages that support the plethora of creative disciplines that fit under arts’ ample umbrella. There are famous performance artists, landscape painters, media artists, potato sculptors and traffic cone artists (I’m not making up those last two genres) residing on their small slice of a ring. Amongst their art clan, they have achieved fame and recognition.

In other words, getting back down to earth, in this atomized world, fame in the arts is relative. One’s fame can seem macrocosmic or microscopic to you, depending on your own coordinates within the system.

What is your approach to rejection as a site of success?

I’ve been a college professor for over a decade, and in that time I’ve taught professional practices courses to emerging artists. Rejection is always a topic of conversation. My maxim to students is “if you’re not receiving some rejection, you’re quite likely not pursuing enough opportunity.” Also, having participated as an artist in the marketplace program myself during my emerging art years, I learned then how important it is to develop a thick skin and an elastic ego. Rejection should fuel you to move forward, not stop you in your tracks. As every aspiring artist learns, in one art history survey or another, the art geniuses of bygone days received countless rejections during their life times. Despite it all, they became FAMOUS.

“The End”

Well, not quite the end. Here’s a confession, each time I receive a rejection I am “wounded,” I feel, against my better judgment, like a failure. This feeling may only last a few seconds, but I still feel the sting, even twenty-four years into an art career —particularly every few years when I complete the art applications marathon. My feelings of failure are illogical. (That’s my inner Spock talking). Having participated on a few award panel juries and knowing statistically that my odds —any artists’ odds— are low, to take rejection personally; or as a sign that I’m not good enough, not bright enough, not in the know enough, nor in the now enough, to be considered at least a legitimate artist, if not always a winning one; is absurd. Still, my inner Vulcan logic flies out the starship window when I read the words “We regret to inform you…”

I get “really human” over rejection.

Some of us more than others are plagued by humiliation, disappointment, low self esteem, and certainly some resentment in the face of rejection, and I doubt any artist takes every rejection in perfect stride. That said I think a heuristic over hubristic approach to not getting the grant, or winning the award, or getting picked up by the gallery is important. By heuristic, I mean being practical and open to self discovery in the face of rejection. Was the opportunity actually the best fit for your work? Was it the right time in your life or your works’ progress for this particular accolade? Is this opportunity worth applying to again and again, thus increasing the odds that one day you might reap its benefits? I ask myself those and other questions, avoiding the sour grapes mentality as much as I can. The “I’ll have the last laugh some day, when I’m famous and ‘you’ (organization, jury, gallerist) will feel humiliated in not recognizing my talent” fuels some people (and certainly on occasion I have harbored these feelings too), but that mantra rings hollow after a couple of years, and certainly after a few decades, when you find more and more that you’re incredibly thankful and hopefully humbled by the fact that circumstances still exist that allow you to make art —whether they include an economy that doesn’t require you to labor 16 hour days to subsist, or a government that doesn’t imprison you because of non-conforming themes in your creative output, or a group of friends and family who believe in you— you’re still making art. This doesn’t mean you lose ambition for your art, you just let go of some of the ambition for your ego.

Back in the snail mail era, one could usually tell when their awaited parcel was a rejection, based on how light the envelope was. Now rarely do we get to weigh our rejection parcels delivered in electronic form, and I no longer keep a pile of rejection letters in a corner to goad myself on. I don’t need to anymore. Rejection is real, it is palpable, but it can be weightless in the grand scheme of your art career, if you let it be, if you let it go.

From “Until the End of the World” HD 3D animated video, 6 min, 2017

Any thoughts on income and financial stability and success?

I’m going to be frank here. Yes, I know I’m Carla, but when I’m Frank I’m more candid, (sorry, I’ll probably commit a pun or two again in this interview). Frankly, I got quite pissed off at the world, at my lot in life, at my humble origins, after I moved, at 24 years old, to New York City. I was from proverbial Podunk, USA. I had a small income. I had no family within a 500 mile radius. I knew two people in the city, and I had very little financial stability. It was here, in New York, where I have lived ever since, that I truly discovered that income and financial stability equals success like two plus two equals four. It’s not the only equation by any means, but it’s the default equation for the most generic definition of success.

One of my early day jobs in New York was as a decorative painter working in the Hamptons. Our wealthy clients preferred “artists” who painted, over “workers” who glued, patterns onto their walls. I suppose even painted wallpaper fits into the aura of scarcity, the pretense that fuels so much of the high finance art world. Don’t get me wrong, I was happy for the work, because that meant I could continue to live in the city, and to maintain my capital A art practice in the evenings and on weekends —well, that is, when I wasn’t assisting other artists, waiting tables, doing temporary office work, working at a gallery, managing an art bookstore, interning for free to learn video editing, or teaching myself computing, to finally elevate myself out of the low wage status that an MFA in painting had provided me. Of course, because the story I’m sharing with you is not unique, on top of rent and art supplies, I had student loans. By the way, last year at 47 years old I finally paid off all of my student debt.🎉

Now, back to being pissed off. Through working jobs in the arts and “distinguished” crafts, and in going to gallery openings and their after parties, I soon discovered that a large percentage of the successful artists and art aficionados I was meeting, or more often, getting in close proximity to, had come from wealthy, or at least, significantly upper middle class backgrounds. I was meeting “go-getters” who’d never had to go or get after their dreams like I felt I had. Good goddess, I’m sure they were sent to the “right” pre-schools in preparation for joining the New York, and world, art elite. They’d traveled extensively, been schooled “ivy-leaguedly,” and had formed friendships strategically. Their parents and their parents’ parents had done, or made, or purchased significant, if not historic, things. They were, and I suppose they still are (who am I kidding using past tense?), the winners that history favors —in the positions of privilege where the “luck of success” occurs far less randomly than to those in the lower echelons. So yes, I was pissed off, but not at any one of these people, “luck” really was bestowed to them upon birth I rationalized. I was furious with a system perpetuating cavernous gaps between the haves and the have-nots. Simultaneously I was furious at my not being on the right side of the gap in the very system I found inequitable and shallow. It’s cognitive dissonance, and I think it’s something many artists grapple with in pursuing the American (or the French, Japanese, South African, British, German, United Arab Emirates, Mexican, Canadian, etc…) Art Dream, i.e. an “anti-capitalist” capitalist dream of success.

I’m not pissed off anymore, well not in my twenty-four year old vehement, unaware of my own privilege, thinking the world owes me something, and by the time I’m thirty I’ll be “discovered,” kind of way. After a few years in New York, I recognized that if I was going to survive as a person with the “I cannot not make stuff” impulse, the impulse that had been driving me towards a career int the arts since my childhood —back when I was free to just revel in the joy of making, because my parents provided me with shelter and food and safety, and that thing even higher on Maslow’s pyramid, encouragement— well, for that “me” to prevail as an adult, I needed to reassess my definition of success in the arts. So, I threw away all of my paintings, the medium that I had defined myself by; I was a painter before I was an artist. I destroyed the objects that I once believed would provide me entrée into the glamorous world of fine art. I wasn’t enjoying making paintings anymore, particularly as my thoughts on class and gender in relation to artistic success were evolving.

As humanity was approaching the end of the twentieth century, I discovered I had a proclivity for working with digital technologies. I found joy in this work, in this play. I could build worlds in my computer, that I could never afford to build in a physical space; and regarding income and financial stability, with computer skills I could earn a better wage at my day job. Letting go of the mythology, instilled in me throughout art school, that earning a living through commercial means is “selling out,” I made new negotiations with myself, not through received knowledge, but through looking critically and honestly at the art world I’d had blind faith in. After several years working in the commercial world, which I admit can be soul-sucking, while maintaining my practice as a digital artist (by now I should just say artist), in 2005 I re-entered academia, as a teacher this time. I love teaching, and it is the esteemed day job a mid-career artist will admit to having at an art opening. Few people, I’ve found, like to talk about their day jobs at openings, but if you’re a professor, your job garners respect —if only more professorships provided stability along with prestige. The exploitation of adjuncts working in art schools too often perpetuates the vicious cycle of financial instability so many artists face throughout their lives. The inattention paid to the working artists’ plight I see as a hindrance to humanities’ success.

How do you define success in the arts?

These are examples of success to me:

When you’re compelled to get to your studio, to make something—even if your studio also functions as the bed you sleep in and the laptop you use for paying bills with— you’re setting aside the mental space and the time for art to be conjured.

If you’re finding some kind of fulfillment in the process —first beginning in the studio that is your mind, then sifted, translated, remapped and reconfigured into a representation: an object, an experience, or event; one that exists outside of just you, beyond your innermost core—you are “succeeding” as an artist.

If this translative act feels deeply personal to you, no matter how philosophical or academic or farcical or absurd the content may be, but you are equally compelled to share it in such a way that another person experiences it with recognition, as if its part of a pattern, to which you both belong, in the expression of human, earthly and cosmological conditions, I’d say you are succeeding in art. Art is communication, and art is a gift.

After feeling the grief, love, anger, happiness, forlornness, redemption, empathy, hostility, fact, and/or curiosity that sparks you to create a work of art, you recognize that there is still a long distance to travel from inspiration to manifestation. The process through which you make art requires your time, commitment, and steadfast belief in its intrinsic value and role as a progenitor for your art. Devotion to your practice leads to success.

Do you have role models for success and who are they?

Yes, I cannot imagine navigating an art life without having my mentors and role models, many of whom, through their struggles for inclusion and recognition, have provided a path for myself and so many others to actualize our practices.

The artist Lynn Hershman Leeson is very significant to me. She is one of my sheroes. I saw her film “Conceiving Ada” in the late 1990s. It was my first introduction to her work, and I was blown away. Lynn’s commitment to a future vision, that has extended far beyond the more myopic preoccupations of many in the mainstream art world, has continued to provide me with inspiration and fortitude. It’s fascinating that curators and critics are only now truly recognizing how prescient her work has been all along. With screenings and exhibitions at MoMA, the Whitney and ZKM, she is successful in the eyes of a much larger art audience today, however she’s been recognized as a pioneering and successful artist by colleagues, art students and new media artists for well over 30 years.

Artists Claudia Hart, Lorna Mills, Michael Rees, Will Pappenheimer, and Tamiko Thiel [who also participated in this interview series-Ed.] are all artists who I look to as models for success, particularly in their contributions to emerging media forms. Like Lynn, they were the people doing the astonishingly cool things before everyone else realized they were cool.

That spirit of innovativeness, tenacity and generosity lives on in the practices of several young artists who I respect a great deal, including Gretta Louw [also part of this series-Ed.], Angela Washko, RAFiA Santana, Faith Holland, Lajuné McMillian, Morehshin Allahyari, American Artist, Cao Fei, and Alfredo Salazar-Caro.

My final listicle is of an art historical flavor. It includes Philip Guston, Suzanne Valadon, Artemisia Gentileschi, Louise Bourgeois, Hieronymus Bosch and Giotto di Bondone – I studied painting at a school where Guston had taught (many years before I arrived there), and coincidentally we share the same birthday. I have always felt a very strong connection to his work, particularly to his late work, where he resisted the art establishment and made pictures that he felt truly represented his time. Valadon, an autodidact, likewise bucked the conventions of nineteenth century “lady painting” focusing on the female nude throughout her oeuvre. Gentileschi in the seventeenth century established herself as an artist who painted historical and mythological paintings, rendering women with more agency and strength than her male contemporaries. Bourgeois’ work, the rawness of her drawings particularly, were quite significant to me as a young artist. I got to attend her Sunday Salons twice in New York, providing me with the opportunity to share my work with her. She was a tough critic by the way. Bosch and Giotto have long been favorites, for the enigmatic and eccentric quality of Bosch’s painting, and the amalgam of Medieval and Renaissance perspectives colliding in the fresco cycles by Giotto.

Which advice on success would you give your 18-year-old self?

Slow down and speed up.

A caveat, when I was eighteen I was still far, far away from any kind of art world we’re having a conversation about. As I mentioned earlier, I was coming from a small town. I was attending an in-state school, because that was all I could afford, making paintings far more illuminated by the past than the present. Still, in the context of all the different art worlds one can inhabit (there are many outside of the mainstream contemporary art world, although none on Saturn yet to my knowledge), I would tell myself “slow down Carla, on your outward fascination with all that seems to glitter about the art life: success, fame, fortune and notoriety. Speed up on your inner investigation of what you have to say and how you can instantiate it as form." I’d also say to myself, find a community of peers who you share passion (not just ambition, and certainly not just “interest”) with. Art that is truly responsive to its time does not, cannot, arise from a vacuum. I say this because I allow for the existence of a collective conscious that we are connected to through an array of frequencies. This is not something I believe in, it’s something I intuit to be true. So the idea that art pops out of a single individual’s head, fully formed and autonomous, like Athena from the head of Zeus, is preposterous to me. It’s a great myth, but a tired explanation for artistic genius. We are social creatures. We are storytellers. Art arises out of our communal experiences, and it stays alive through our gifting it to one another.

There’s one more reminder I’d give to 18-year-old me. I am an only child and was told early on, perhaps even before I exhibited such tendencies, that I was an over-achiever and highly success-oriented, so hey young Carla listen up, “to have self worth you don’t need to be the shiniest star in the art community, or to continue with the metaphor, the shiniest star in the constellation you’ve formed a bond with. A cohort of bright, empathetic people who feel creatively akin to each other, can form a constellation far more radiant and symbolic than a single gaseous spheroidal body (i.e. a star). You all may one day be the “Big Dipper” that guides others along their creative paths. Just as likely, your constellation may only be perceived by a few human eyes, instead of millions. You may not be picked up collectively, or individually, by the “Hubble Art Telescope.” Either alternative is possible, and a million others, if you recognize the possibilities of forking paths. Continue Carla, continue to be mystified by the universe and remain grateful for your coordinates within it. Recognize that success comes to you every time you choose to actively and compassionately engage with your senses, releasing the particles of your inspiration into the atmosphere of this curious and wondrous thing called life.

Origins of the Universe, 2017-2018 3D printed polyamide with copper plating, smart phone, fixed video, pedestal, plexi vitrine 5 x 10 x 13.4 in, sculpture 54.75 x 14 x 17.5 in © Courtesy of the artist

Your thoughts on success in the arts and race/ gender

As I began answering this question, the United Colours of Benetton advertising campaign, from the early 90s, popped into my head (and no Athena popped out). I remember thinking at the time in looking at those ads that we were well on our way to achieving multicultural harmony in a globalized world. I was young and naive and obviously could not have been more mistaken. By the mid 2000s I was finding myself in conversations with other Gen X female artists who refused to, or were afraid to call themselves feminists. They feared it would hurt their chances of success in the art world. At this time, around 2005, the representation of people of color and female identified artists in the art world was still very small compared to the number of white male artists represented in museum exhibitions, galleries and in auction houses.

Today, I am encouraged that many artists have once again taken up the feminist mantle, expanded by its intersectional dimensions, due in large part to the efforts and activism of Millennial and Gen Z generations. Also there has been a sea change in the arts over the past few years, in response to the #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo movements. Curators, administrators and trustees representing major art institutions are waking up to the realization that their programming, acquisitions and funding structures need to support a much more diverse population of artists. Indeed museums and galleries across the United States (I don’t have statistics on other countries but it seems to be global) are stepping up, and providing platforms for artists fighting for equity, inclusion and justice.

I’m not sure if the art pool is altogether public yet, but as private pools go, it has taken steps in the right direction towards opening up its membership. Thankfully some intolerable art world miscreants have had their passes revoked too. They didn’t seem to get the memo that their abuses of power would no longer be tolerated —or, at least, would no longer be tolerated in certain sectors of the arts. Unfortunately there’s another memo circulating too, in the heavy winds following along the tidal wave that is Donald Trump’s presidency. Across the planet a swell of authoritarian leaders, supported by a populist surge, have taken control. These violent waves are crested with white supremacist and men’s rights groups spewing hate-filled messages that I once believed had all been plastered over by Benetton ads promoting diversity.

Artists, activists, intellectuals, professors, we are currently swimming in dangerous geopolitical waters. Now more than ever we need to strengthen our creative communities, and in the face of dangerous opposition, to celebrate our individual and communal artistic successes.